CHINA: Whatever happened to China’s 2024 Universal Periodic Review?

A hodgepodge of technicalities at Geneva’s Human Rights Council is already resulting in nothing. This is how the United Nations functions in 2024.

by Marco Respinti

Bitter Winter (20.02.2024) – On January 23, 2024, the United Nations Human Rights Council’s (UNHRC) Universal Periodic Review (UPR) Working Group examined, for the fourth time, the human records of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) at the Palais des Nations, which hosts the United Nations Office at Geneva (UNOG), Switzerland.

A forest of confusing acronyms

A “State-led mechanism that regularly assesses the human rights situations of all United Nations Member States,” the UPR is one of chief tools of the UNHRC. It was established on March 15, when the United Nations (UN) General Assembly created the UNHRC itself to replace the obsolete UN Commission on Human Rights (UNCHR), founded in 1946.

UNHRC operates in close cooperation with the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (UNHCHR). Though their mandates may overlap, of course they are different agencies. UNHCHR, “the leading UN entity on human rights,” is committed to the promotion and protection of human rights as per the 1948 “Universal Declaration of Human Rights,” while the UNHRC, an intergovernmental body, is mainly a place “to discuss all thematic human rights issues and situations that require its attention throughout the year” as well as “for addressing situations of human rights violations and making recommendations on them.”

But since also UNHRC is “responsible for strengthening the promotion and protection of human rights around the globe,” of course per the 1948 “Universal Declaration of Human Rights” as well, the layperson may easily confuse them (or their acronyms) and not comfortably get who’s who at a glance. The scenario is further complicated by the existence of another agency—quite different in itself, but sometimes not straightforwardly perceived as such by the general public—, the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).

What is the UPR?

UPR “calls for each UN Member State to undergo a peer review of its human rights records every 4.5 years.” Since the first periodic review in 2008, “all 193 UN Member States have been reviewed three times.” The fourth cycle of review began in November 2022 with the 41stsession of the UPR Working Group, whose operation of scrutiny is divided in three two-week long sessions per year, each reviewing 14 countries, thus 42 annually. The PRC was in the group of 14 scheduled for review at the 45the session of the Working Group, from January 22 to February 2, 2024.

The first, second and third UPR of the PRC were held in February 2009, October 2013, and November 2018. “Bitter Winter,” a magazine at that time and until December 2020 dedicated only to religious liberty and human rights in China, began its operation under the cogency of the 2018 UPR of the PRC. Online since early May that year, one of first participations of “Bitter Winter” in a public event in person was a pacific demonstration hosted in Geneva by organizations representing persecuted groups on November 6, 2018. It was the very day of the third UPR of the PRC and resulted in a disappointing document in March 2019.

Much of that failure had to do with the UPR machinery itself. The UPR Working Group includes the 47 Member States of the UNHRC. Three of them are chosen randomly for each of the country in review and, known as “troika,” serve as rapporteurs. At the review, the country under scrutiny has abundant time to present a national report. This is examined by all the countries that, out of the 193 Member States of the UN, register to take the floor.

The total time of the review for a scrutinized country is 3 and a half hours; thus, the number of countries that registered to take the floor at the review influences the amount of time that each of them has at its disposal. Then a final report is prepared by the troika and goes for adoption at a UNHRC regular session (they are three per year).

Chinese propaganda

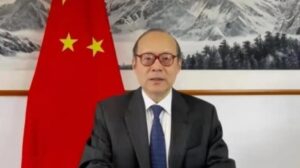

On January 23, the UPR of the PRC was broadcasted live. The Permanent Representative of the People’s Republic of China to the United Nations Office at Geneva, Chen Xu, leading a delegation of representatives from some twenty Chinese ministries and from Xinjang, Tibet, Hong Kong, and Macao, presented a long national report. It was an exercise in blatant propaganda as usual, exemplified by ridiculous statements like these: “China upholds respect for and protection of human rights as a task of importance in State governance, fostering historic achievements in the cause of human rights in China. We have, once and for all, resolved the problem of absolute poverty, thereby attaining our first centenary goal of building a moderately prosperous society in all respects on schedule. We will continue to develop whole-process People’s democracy, promote the protection of human rights and the rule of law and resolutely uphold social equity and justice. […] We uphold the equality of all ethnicities, respect the religious beliefs of the people and protect the lawful rights and interests of all ethnic groups” (I, C, 4). “China is developing whole-process People’s democracy in all respects, and its people carry out democratic elections, consultation, decision-making, management and oversight […]” (II, C, 1, 11).

Beijing prepared the meeting with the usual, intense lobbying campaign. The PRC Ambassador’s speech was 70-minutes long. The 160 registered countries had 45 seconds each for questions and evaluations. Some of them mentioned violations of human rights and repression on ethnicities, but time limits prevented incisiveness. Many were rather shy, with the possible exception of the United Kingdom, Canada, the United States of America, the Czech Republic, and Slovenia. Some even thanked the Chinese regime for money they received. And the most horrendous methods of persecution operated by the Chinese regime on innocent people went totally unaddressed, for example the dreadful practice of forced organ harvesting (FOH), now fully exposed and documented.

The delusion was evident in all the press releases and comments by the organizations representing the diasporas and the persecuted. Two side-events, held one after the other in the same Room XXVI of the Palais de Nations, went unacknowledged, even if the UNHRC rules admit NGOs’ contributions to the debate. Accompanied by an important document, the first of those side-events was dedicated to FOH—and “Bitter Winter” partecipated—, the second focused on the persecution of Tibetans (attracting in the audience also other persecuted peoples, such us the Uyghurs).

And now what?

On October 11, 2023, it was the time to select 15 of the 47 Member States of UNHRC, elected periodically at rotation. The PRC was already one of those 47 before that election and was reelected as one of those 15. Not only the PRC but also others within those 47 have quite peculiar ideas on human rights, a fact that urges all to reflect upon the criteria by which that group is selected.

As to the troika guiding the 2024 UPR of the PRC, and now working on its final report, it is composed by Malawi, Albania and Saudi Arabia. Malawi is one of the many PRC’s vassals in Africa, also severing its ties with the Republic of China (Taiwan) in 2008 in favor of Beijing. Albania stands on the Balkan route of the PRC’s “Belt and Road Initiative.” And Saudi Arabia is a notorious partner of the PRC, a Muslim state that even plauds at the Chinese regime’s persecution of fellow Muslims, the Uyghurs and other Turkic people in Xinjiang (that its non-Han inhabitants call East Turkestan), alongside other Muslim (or Muslim-related) entities like the Organization of Islamic Cooperation and the Palestinian Authority.

From its draft, it seems that the final report of the Working Group on the 2024 UPR of the PRC will be presented at the UNHRC’s 56th regular session, scheduled from June 18 to July 12. But then what?

The final report will contain observations and considerations, evaluations and possibly some criticisms, but it will be a compromise by nature, its actors being the PRC, the registered 160 countries which took the floor, including those which praised the Chinese regime, and the pro-China “troika.” So, that document won’t affect the PRC in any case and won’t change the staggering record of the Chinese regime in human rights.

It already happened before and the interminable statement read by the PRC Ambassador on January 23 confirmed it: “The Chinese Government,” he said, “accepted 284 of the 346 recommendations put forward by various countries in the course of the third cycle of the universal periodic review. China attaches great importance to follow-up work. Immediately after the review, the Government brought the relevant domestic departments up to date via a cross-sectoral coordination mechanism, clarifying the division of labour and programme implementation among the various departments. It prepares regular overview reports on the status of implementation, paying particular attention to hearing the views of non-governmental organizations. The resulting advances are reflected in this report” (I, B, 3). The unchanged and worsened situation of human rights in the PRC from 2018/2019 to 2024 demonstrates that these are only lies hidden under a polished façade.

This is why the PRC doesn’t fear the “Chinesely correct” judgment of the United Nations and is quite able to turn to its own advantage also the timid criticism of its acts and policies that at times may come from it. In the meantime, despite all the bureaucratic precision of the UN agencies’ rules, procedures and limitations, the summary of the proceedings of the review process of the PRC that the Working Group promised for February 9 in its online draft of its final report has still not been published—and this speaks for itself.

Chinese diplomat Chen Xu (from Weibo).

*************************************************

Marco Respinti is an Italian professional journalist, member of the International Federation of Journalists (IFJ), author, translator, and lecturer. He has contributed and contributes to several journals and magazines both in print and online, both in Italy and abroad. Author of books and chapter in books, he has translated and/or edited works by, among others, Edmund Burke, Charles Dickens, T.S. Eliot, Russell Kirk, J.R.R. Tolkien, Régine Pernoud and Gustave Thibon. A Senior fellow at the Russell Kirk Center for Cultural Renewal (a non-partisan, non-profit U.S. educational organization based in Mecosta, Michigan), he is also a founding member as well as a member of the Advisory Council of the Center for European Renewal (a non-profit, non-partisan pan-European educational organization based in The Hague, The Netherlands). A member of the Advisory Council of the European Federation for Freedom of Belief, in December 2022, the Universal Peace Federation bestowed on him, among others, the title of Ambassador of Peace. From February 2018 to December 2022, he has been the Editor-in-Chief of International Family News. He serves as Director-in-Charge of the academic publication The Journal of CESNUR and Bitter Winter: A Magazine on Religious Liberty and Human Rights.

Photo 1: Much ado… but about nothing. AI-generated elaboration of a political cartoon about inconclusive UN debates.